ARCHIVE:

Designer Collective from Istanbul Bilgi, Mimar Sinan and MEF University

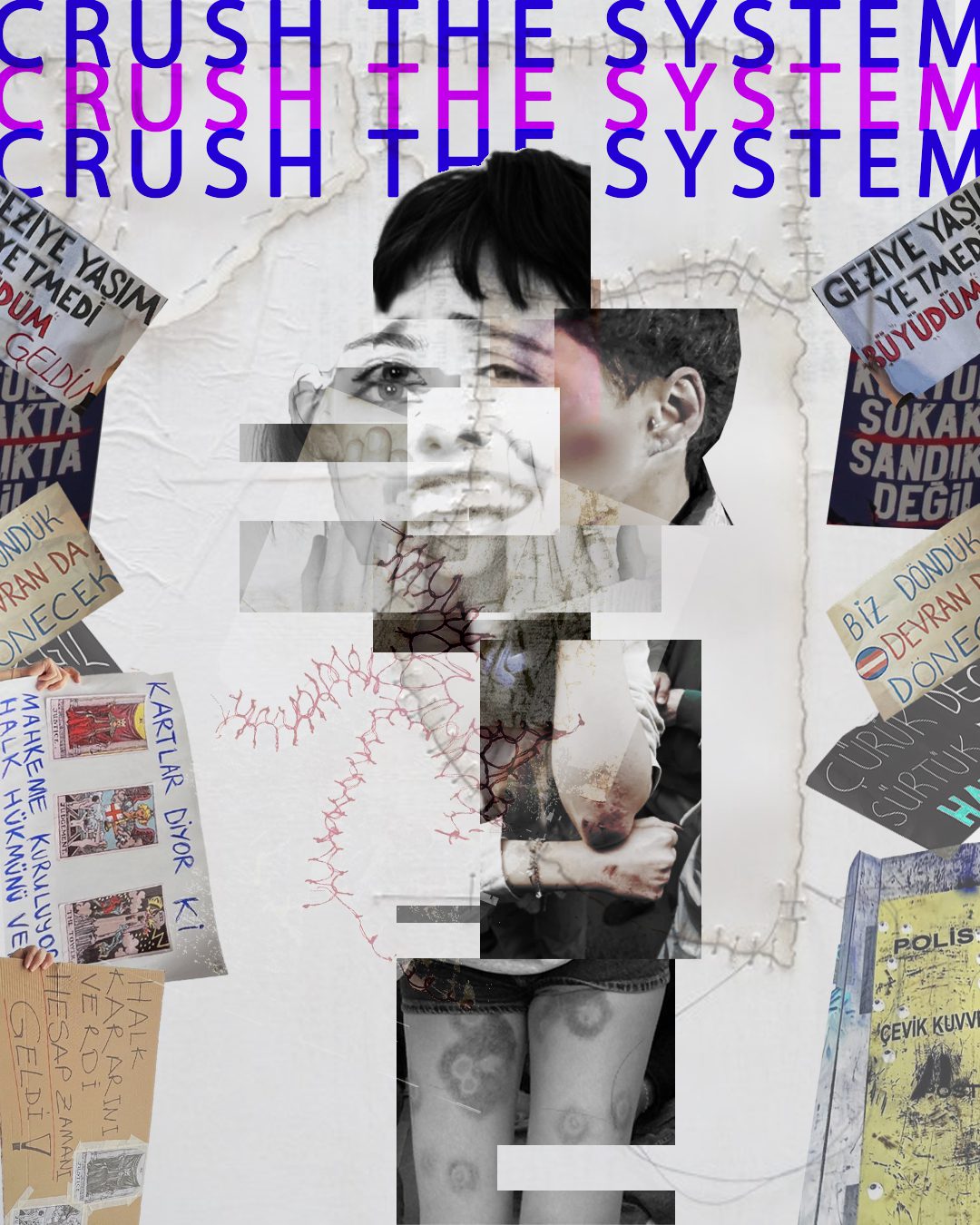

We are designers who have witnessed this resistance—those who aim to map the process, to make it visible, to remember and to remind. We have come together through the power of collective creation. We dream of being united, designing together, and reflecting this unity onto space. As we experienced the resistance in faculties that were shut down, in spaces that were dismantled, under sieges, and in silenced forums, space has become not only something we draw, but also something we intervene in, defend, and strive to reclaim. We found each other not in competition, but in solidarity. We stepped outside the roles assigned to us; we crossed the boundaries of rivalry and began to construct a space of collective support. We carry it to the streets, the squares, the city itself. We believe that spaces should be designed with a spirit of freedom, equality, and without segregation. We are here not only as designers of space, but as subjects who question it, transform it, and multiply it.

Instagram Accounts:

We are students who have never met each other, yet breathe the same air of oppression. Some of us are women, some men, and some neither. Among us are Kurds, Alevis, Armenians, migrants, and refugees… Some live in state dormitories, some cannot find housing, and others live in hiding from their families. Each of us is a different world, a different story. As we emerge from the same metro stations, walk the same streets, and strive to earn the same diploma, we have come to see that although the burdens we carry differ, the language of the oppression we endure is all too similar. We are left alone, rendered invisible, pushed into corners.

But we do not accept this loneliness—and we know another life is possible.

Our solidarity begins not by suppressing our differences but by seeing, understanding, and embracing them. Though we speak different languages, we listen to each other’s voices, acknowledge each other’s presence, and respect each other’s ways of enduring.

Everyone who is forced into silence in school hallways, who fears being identified on the streets, who places extra shoes at the door of their home—all share a common desire: for a life that is safer, more just, and freer.

This togetherness is born not of agreement, but of a shared feeling.

Our strength does not lie in our sameness but in our ability to stand side by side with our differences.

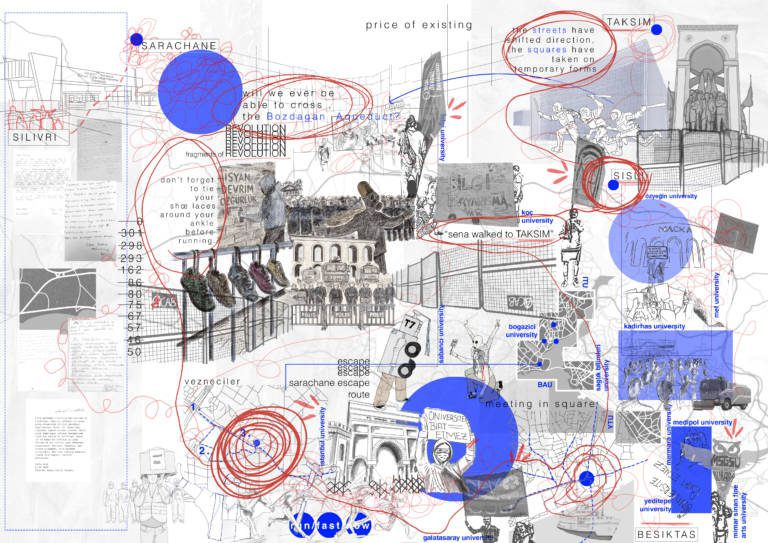

Student Collectives and the Urban Map of Hope: The Resistance and Reconfiguration of Space

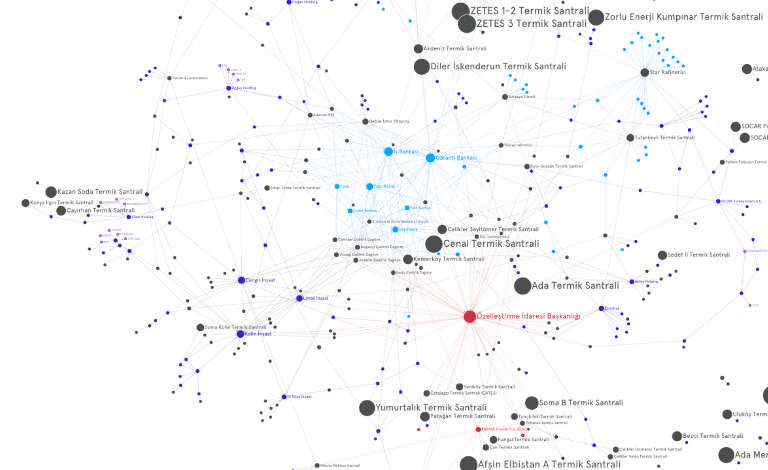

For years in Turkey, the political pressures we have endured have not only targeted our thoughts but have also constrained our bodies. We live in a city order designed to keep us away from streets, squares, and encounters. This is not just a reflection of political turmoil—it is the spatial projection of social polarization. And this projection is constructed not only with walls and fences but also through the control and direction of our movements.

As students, we have been systematically isolated within this system. But something happened.Since March 19, the events have created a space to question this order. A new story began—one of those who refused to remain silent in the face of oppression, those who grew tired of loneliness, and those who took to the streets. In this story, the city is not merely a backdrop; it becomes a protagonist.

Topography of Resistance in the City

Though the first barricade that collapsed in front of Istanbul University echoed widely, that echo was stifled under the shadow of riot police. During this process, Istanbul transformed into a topography of resistance. Each space took on new meanings.

Saraçhane, despite being a central public space, resembled a fragmented void. In these voids, different segments of society infiltrated and encountered one another—perhaps for the first time—and were forced to discover unity. The crowds gathered in front of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality building questioned whether public buildings truly belonged to the public. The narrowness under the Valens Aqueduct revealed the urban decay caused by shrinking paths. The Vezneciler Metro exit became a point of infiltration for every protester—but also a part of the blockade line.

As the night wore on, one question became clearer: Will I make it home safely tonight?This question might have crossed everyone’s mind, but for some, it was part of a much deeper fear. Women, LGBTQ+ individuals, minorities—those rendered invisible, limited, and silenced every day in this city—know that the question “Can I get home safely?” is not just a fleeting concern but the essence of their daily life. While their every step is already monitored, simply daring to exist in public becomes a form of resistance.

As we try to raise our voices against a system that destroys hope and safety, we also face the possibility of surrendering to the fears produced by that same system. The anger that pushes us into the streets becomes a threat in those very streets. And thus, we are caught between the price of being visible and the helplessness of remaining invisible.

Spatial Inaccessibility and Permeability

Although horizontal transportation lines seem efficient in terms of mobility, they are impermeable for action. The city functions for transport, not for gatherings.

Şişli exemplifies this contradiction. While the area in front of Cevahir Mall appears as an open space, it is part of an accelerated system of movement that allows no room for temporary assemblies. The Metrobus line, metro exit, overpasses… everything is designed for transit, not for pausing.

Osmanbey Metro connects to one-way street systems. The route to Nişantaşı differs demographically from Saraçhane in terms of visibility and public density. In this kind of “comfortable chaos,” a sense of safety can emerge.

Maçka Park, however, was an exception. It became a space for breathing and forming solidarity. The roads leading to the park interrupt the city; a parenthesis is opened where urban life is momentarily suspended by protest. The collective that marched from Maçka carried accumulated anger, invisibility, and demands for rights—and while moving through the normative existence of Nişantaşı, it confronted the public with diversity. At the end of this route, the front of Şişli Municipality became another space for public confrontation.

The streets of Bomonti, in contrast, resemble an alternative artery in the urban memory: massive, winding, multilayered. Here, resistance can take root within invisibility. On one hand, it is a refuge; on the other, it conflicts with the desire to be seen.

Scattered Gatherings and Resistance Practices

The dispersion of protests from Saraçhane into the city’s arteries was a strategic attempt to open up urban space for struggle. But the city’s deterioration made intersection and convergence difficult. The structure—unsuitable for spontaneous gatherings—also had the potential to render resistance invisible.

In this sense, Beşiktaş Square posed a meaningful contrast. Centrally located with access to ferry lines, bus routes, and Metrobus, it facilitated convergence. Though heavily policed and surveilled, the presence of everyday citizens and tourists acted as a kind of “civil shield.” This practice of dispersion, aimed at disrupting daily life, proved effective. Beşiktaş was the gateway to marching toward the Golden Horn (Haliç). But while the city opened to the sea at the Golden Horn, it closed to resistance: you were either trapped on a bridge or redirected to Saraçhane.

On May 1, the disruption of the city’s transportation network went beyond a mere security measure—it was an expression of fear. The normal flow of life was halted; every street in Mecidiyeköy was blocked. Roads to Taksim were sealed off. This is the result of long-standing urban decay. The ease of intervention stems from narrowed public spaces, the suppression of urban memory, and the spatial isolation of dissent. During this time, even small gatherings became excuses for detentions. This is what they fear most: that we remember the public, the collective.

The Loss of Safety and the Exclusion of Space

That police—once expected to symbolize safety—have become a threat for many is no coincidence. This transformation became even more visible during the nights in Saraçhane. The disproportionate use of force left lasting marks not only on bodies but also on collective memory. That night, people approaching a young person in need had to say: “Don’t be afraid, we’re not the police.” This sentence revealed a stark truth: safety was no longer expected from the state, but from the people. The police pepper-sprayed, kicked, and beat those who had fallen, were crying, or pleading. One young person who lost their eyesight because of this violence will now exist in the city not just as an individual but as a witness and bearer of state brutality. Not only our physical integrity but also our personal privacy is under threat. With cameras in hand, the police no longer represent safety but surveillance. This points to a surveillance society in which even digital traces become inescapable.

Some of the slogans echoing through the streets revealed another danger: racism, sexism, and various phobias. These discourses showed that space is not only a site of resistance but also one where exclusion can be produced. The city’s conflicted topography makes these contradictions even more visible. Being excluded, subjected to violence, or silenced in spaces that should belong to the public stems both from the oppressive tools of the state and the exclusionary reflexes of a population that cannot internalize social pluralism. That’s why hope must be built not merely on coming together, but on a foundation of inclusive, egalitarian, and safe encounters. The city must be transformed ethically and socially. Hope can only survive in a space where everyone feels safe and seen.

The Twilight of a Generation

Among these crowds were many young people who have never known another government. A generation raised in fear, silenced through intimidation, trapped in inhumane conditions in public dorms, deceived with promises amidst deprivation… These students walking the streets were carrying not just their bodies but also their disappointments. Because the only thing ever offered to them as “hope”—a diploma—no longer meant anything. In a system where merit is obsolete and loyalty is rewarded, these young people are now questioning not only their future but their very existence today.

This is why they join the movement…

Loneliness, Encounter, and Hope:

During the protests, streets changed direction, squares took on temporary forms. Dead-end paths opened, open roads closed. The city reacted like a living organism, and we experienced this reaction.

What we realized in this experience is this: People are lonely. This loneliness is not only political but also spatial. Encounters are increasingly reduced. The possibility to gather, be visible, stand together is systematically suppressed. The city is now defined not by gatherings but by dispersals.

But within this loneliness, we also carry hope because we see hope not as an abstract expectation but as a spatial practice that can be reorganized. We know that in this city, by touching each other, we can build trust, that at night in Taksim we can walk with transparent shields in our hands, that by moving together we can create new paths.

And that is why we say:

Hope is a matter of spatial organization.

We seek hope in the city, in the map of our journeys, in the rhythm of our gatherings, and in the persistence of our demands for visibility.

That is why: The city must be rewritten.

Note from İstanbul Architecture Diary:

As a special edition dedicated to architecture students who organize in solidarity collectives to voice shared struggles and hopes, we — the editors of the Istanbul Architecture Diary — invited them to share their hopeful memories and motivating encounters. They were also encouraged to describe the values, demands, and visions their collectives stand for, or imagine the kind of education and university life they wish to see in light of today’s realities.